Combining Family Life & Professional Life

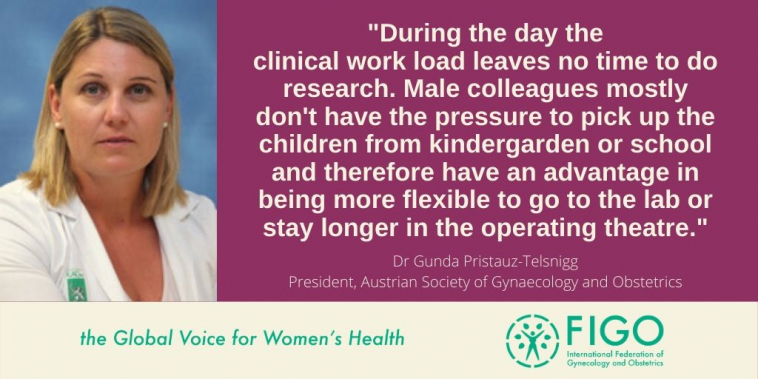

This month FIGO speaks to Dr Gunda Pristauz-Telsnigg, President of the Austrian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, about her journey as a female OBGYN and her vision for the future of women’s health in Austria.

‘I am Generation Equality: Realising Women’s Rights’ is UN Women’s theme for this year’s International Women’s Day, marking the 25th anniversary of the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action.

This month FIGO speaks to Dr Gunda Pristauz-Telsnigg, President of the Austrian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, about her journey as a female OBGYN and her vision for the future of women’s health in Austria.

As a child I dreamed of becoming a professional tennis player, and I greatly admired Steffi Graf. But since my training off the court day by day was limited, my parents insisted that I finish school. My father was a very wise man who grew up after the Second World War, and he had wanted to become a doctor himself but his father – my very strict grandfather - wouldn´t allow it.

So, my father had to become a teacher. Ever since I was little my father has been reading medical articles and was fascinated by science, being especially interested in medical science and he actively encouraged me to study medicine. My father gave me the advice that if I delve deeply into medicine my work will be a profession, my profession will always be interesting, and that my field would be sure to evolve rapidly.

And he was right! Work that you love makes every day an exciting new adventure.

Challenges in the field

As a young woman, whether a doctor or not, you have dreams and visions of your future regarding family, job, hobbies and health. Therefore it was very challenging for me to, by day, to cope with female patients who had to realise that their future would be illness, tears, sadness and death. When I was 27 I had to tell a young lawyer who was the same age as I, who had just married and was planning her first pregnancy, that her cancer had come back and had spread to her lungs and liver and that she was going to die. Her face will be in my mind forever. She sadly died some months later.

Fortunately we work in a team and can talk to colleagues and psychologists about these challenging and dramatic experiences, and we do treat many patients successfully. But I think it is hard for young female doctors in OBGYN to counsel young women with life-changing or life-threatening illness.

When I started my scientific career I was already a mother of three little boys (7, 5, and 1). I was very lucky to have my parents and my sister to help me look after the kids if I was late from work or on night calls. But especially for young female doctors and mothers who don´t have their family close, it is almost impossible to stay in the hospital to do research after working hours.

During the day the clinical work load leaves no time to do research. Male colleagues mostly don´t have the pressure to pick up the children from kindergarden or school and therefore have an advantage in being more flexible to go to the lab or stay longer in the operating theatre.

Combining family life and professional life and research is probably the most challenging issue that young female physicians and scientists face in Austria. Often, they have to decide between research and family and then of course most young women want and decide to have children. We need better and more accessible and flexible childcare, and we need to raise the awareness of the conflicts young mothers and researchers face. We need to make it possible that they can combine family and research and not have to choose between them, even if it takes a longer time to reach their goals.

Specialising in Breast Cancer

During my residency I became interested in breast cancer and started to specialise in this area. Around 2000 the importance of the BRCA mutations became appreciated in families with high rates of breast and ovarian cancer, and the technology became available to test individuals and families. At this time the Department of Genetics at our institution in Austria got new leadership and began germline testing of the BRCA genes. We started a cooperation and built a Genetic Counselling unit at our department. First there were only a few women, but it grew quickly.

Initially we were confronted with the issue that we were just diagnosing the problem but not able to actually help patients with mutations. This spurred us to participate in many studies concerning breast cancer patients with BRCA mutations, and this area has developed dramatically.

Now, after many years of research, specific therapeutic agents (PARP inhibitors) have been found to be especially effective in tumors with DNA instability, such as BRCA mutated breast cancer. I remember how happy I was when I was able to tell these, mostly, very young breast cancer patients that we had a highly effective therapy that is exclusively approved for patients with mutations and that will help cure their disease.

Looking to the future

In Austria we are very proud that just about every person has public general health insurance and access to high quality medicine and treatment. But beyond this we have two main goals for the future in Women´s Health in Austria:

First we are working on making second trimester organ screening (at 20-22 weeks) available to all pregnant women. Currently women have to pay for this special ultrasound exam and this costs €200 to €300. This amount of money can be difficult to get ahold of and therefore the examination is mostly done only by well situated pregnant women, which leads to a disproportion in examinations during pregnancy. We believe this exam should be available to all.

Our second goal is reduction and potential elimination of HPV-related disease. The first part of this is increasing the rate of HPV vaccination. This is now at about only 30% of young people – and we still perform close to 7000 conizations yearly. We need to do better.

The second part of the HPV issue is secondary prevention. Austria does not have an organised screening programme - we have decades-old opportunistic exams based on the annual Pap smear. This has dramatically reduced mortality from invasive cervical cancer, but we still do many, many conization procedures, and the public system does not cover HPV-based screening.

My goal as current president of the Austrian Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics is to strongly push for an organised HPV-based programme. Our goal has to be the elimination of cervical cancer and its precursors and other HPV-related diseases.