From ‘Conscientious Objection’ to ‘Conscientiously Committed’ – How OBGYNS can advocate for bodily autonomy in access to safe abortion

In this FIGO Long Read, we provide a round-up of a recent roundtable discussion hosted by FIGO's Advocating for Safe Abortion Project (ASAP) and Committee on Safe Abortion. Together with partners, we explored the critical issue of 'conscientious objection' and its impact on the availability of and access to legal and safe abortion services.

Recent victories that have improved the legal grounds for abortion in Argentina and Ireland have subsequently demonstrated that although it is critical to fight for legislative change, the availability of safe abortion services must also be addressed, if the right to safe abortion care is to be fully realised. Without this, abortion laws risk becoming a charade in the lives of women, girls and pregnant people who require access to abortion services.

The availability of legal and safe abortion services – and access to them – remains a critical barrier for women, girls and pregnant people around the world. This is in part driven by OBGYNs and other health care practitioners ‘conscientiously objecting’ to perform safe abortions. In order to address this critical issue and explore ways forward based on evidence and human rights standards, FIGO’s Advocating for Safe Abortion Project (ASAP) and Committee on Safe Abortion brought together leading health and human rights advocates to participate in a roundtable discussion on the issue.

Safe abortion services are essential health care

The World Health Organization and FIGO, in addition to other human rights institutions, have stated that abortion is essential and time-sensitive health care. Dr Laura Gil, member of FIGO’s Committee on Safe Abortion and an OBGYN at the National University of Colombia, highlighted the importance of this:

We must recognise what our primary duty as doctors is. And that it is to treat, benefit and prevent harm towards patients, and to make sure that they get what they need, based on their informed consent.

Decisions that a patient makes must be truly informed and autonomous... An abortion is an essential service, and it should be provided to all, to the full extent of the law in the countries that we live in and practice.

The ‘Conscientious Objection’ Mechanism

Dr Gil clarified what ‘Conscientious Objection’ (CO) was and was not regarding abortion services:

CO is a mechanism through which a person can refuse to perform a task… It is a mechanism, not a right itself. And it is essential to understand that CO cannot limit all of the other fundamental rights [of women, girls and pregnant people] that are at stake, such as the right to dignity, health and autonomy.

CO takes place in the context of a very unbalanced relationship of trust in terms of authority and power... [in] a doctor-patient relationship, all effort should be made not to compromise the autonomy and welfare of the least powerful of the relationship – and that is of course the woman or girl.

Dr Gil stressed that if a doctor or a health care practitioner does not agree with abortion, their position cannot be used to deny access to safe abortion services. For instance, information concerning a referral cannot be withheld and patients’ rights cannot change because a doctor wants to protect their own conscience. 'Conscientious objectors' have a responsibility to provide unbiased information and to ensure, in advance, that they are able to refer the pregnant person to a health care practitioner or provider that can provide the safe abortion to ensure no harm is caused to the patient.

Importantly, Dr Gil advised that CO cannot be invoked by a hospital or an institution or any other health worker not directly responsible for performing the procedure (such as administrative staff). She further advised that,

CO cannot be invoked if there is risk to life – like in emergency situations – and also in cases when women seek post-abortion care, or when there is no other reasonable option for referral. In such situations, the doctor or health care worker must perform the abortion.

Unregulated 'conscientious objection' results in unjustified denial of health services

The exercise of CO is legally recognised with set limits in the majority of countries. While legal and regulatory standards explicitly set limits and obligations on health care practitioners to ensure that access to safe abortion services are not disrupted or blocked, in practice the regulation of CO is grossly inadequate. Dr Gil stated that,

Sadly CO has become a widespread barrier for many women to access the care that they need. It is very common to hear that women or girls cannot get an abortion on time or got an unsafe abortion, or didn't get one at all because of CO from the available personnel.

Further, Dr Gil stressed the importance of calling out that when CO leads to delays and harm and undue burden for women/girls and pregnant people to access essential healthcare then it must be called out as for what it is – unjustified denial of health services. This denial of care leads to deaths and disability caused by unsafe abortion, or serious long-term emotional harm from forced motherhood.

Melissa Upreti, Chair of the UN Working Group on Discrimination Against Women and Girls, shared key insights from the working group’s report on CO:

We [UN Working Group] have reiterated that the enjoyment of the right to freedom of religion or belief cannot be used to justify discrimination against women and girls, and therefore should not be regarded as a justification for hindering women's realisation of their right to the highest attainable standard of health.

The impact of CO to the extent that it can effectively deny timely access to abortion has a discriminatory impact. While health care professionals are entitled to their religious beliefs, these beliefs should not be given priority over the duty to provide essential care. Health care providers who put their personal beliefs over their professional obligations toward patients effectively threaten the health care profession’s integrity and its objectives.

Ultimately, according to Upreti, even when CO is permitted, states still have the obligation to ensure that women's access to reproductive health services is not limited.

Moving from ‘conscientious objection’ to ‘conscientiously committed’

The term 'conscientious objection' implies that 'conscientious objectors' are the only ones acting in conscience. This distortion is mediated by stigma. This fails to recognise that abortion providers are driven to act with their ‘conscience’ to safeguard women/girls’ rights… because they believe that they are providing good and ethical care.

– Dr Laura Gil.

Dr Gil stated that the while CO implies that essential abortion health care services are not performed due to a OBGYN ‘conscience’ or a ‘moral high ground’ in reality, based on studies, essential abortion services are often unjustifiably denied.

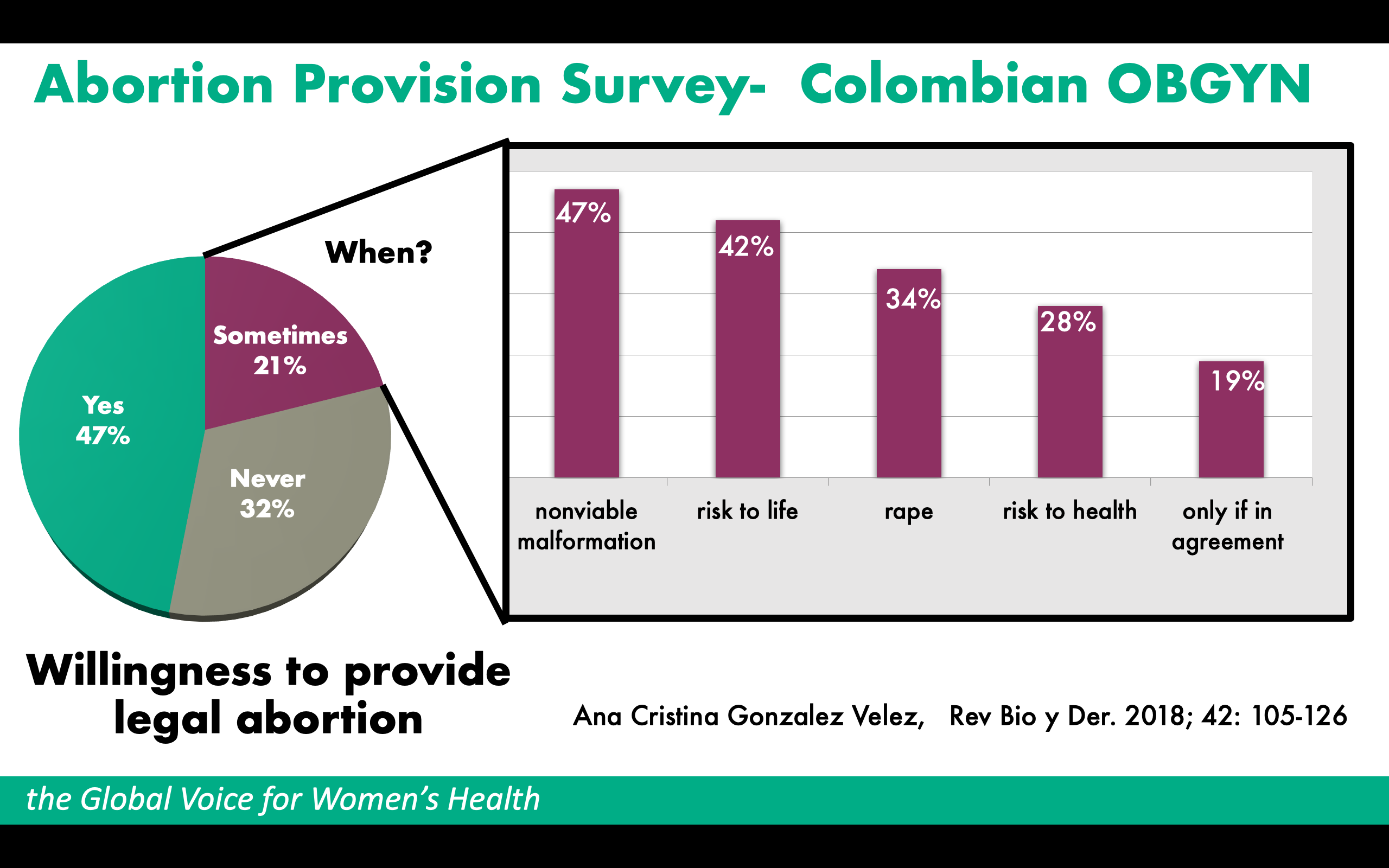

For instance, a study in Colombia on abortion provision revealed that out of all OBGYNs surveyed, 47% stated they would provide abortion services, 32% stated they would never perform abortion services and 21% would ‘sometimes’ perform them. Within the ‘sometimes’ category there were varied responses of when OBGYNs would and wouldn’t perform the abortion (see graphic below).

The study revealed that OBGYNs' ‘conscience’ enables them to perform abortions in some situations, and this can be influenced and informed by the institutional environments they have been trained and work in. Health care practitioners state that their ‘conscience’ does not allow them to perform an abortion, when in reality it is often the fear of stigmatisation for providing abortion care that stops them. Such stigmatising and criminalising environments nurture hostility, especially for health care practitioners who are conscientiously committed to providing essential abortion.

The devastating ripple effects of 'conscientious objection'

Melissa Upreti shared how during a UN Working Group visit to Poland, they found that “in certain areas, there were no abortion providers at all”, and that “there had been attempts to create abortion-free zones”. In addition, CO was not only affecting access to abortion, but also to emergency contraceptive pills. She explained that,

We were informed that access to emergency contraceptive pills, which were previously available over the counter, could only be obtained with a doctor's prescription. Considering the circumstances in which emergency contraceptive pills are typically used, we deemed that this requirement does pose a significant barrier and defeats the very purpose of their use. We were told that not only does it take time to be seen by a doctor, but that many doctors refused to prescribe the pills claiming CO. Even pharmacists had started to invoke the CO clause to refuse the sale of emergency contraceptives, even though that was illegal. We were also informed that emergency contraception and antiretroviral drugs or related information was not being provided to victims of sexual violence.

According to Upreti, the case of Poland shows how CO can have a pervasive impact on access to a range of services, which are all interconnected. This creates a stigmatising environment that undermines access to sexual and reproductive health and rights in very profound ways. In fact, in many cases doctors in Poland used CO to avoid stigma and prosecution, rather than for religious reasons.

Meanwhile, in Argentina, where the new law allows for abortion on demand in the first 14 weeks of gestation, the UN Working Group saw concerning uses of CO. According to Upreti, in Argentina,

CO can be both personal and institutional, and most private hospitals and clinics have institutional CO. And within certain public health institutions, in some instances 100% of staff members are individual 'conscientious objectors', which in practical terms, makes access to safe and legal abortion impossible.

Prohibiting 'conscientious objection': the Ethiopian experience

Ethiopia is one of the few countries where CO is prohibited. According to Dr Mekdes Daba, President of the Ethiopian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, a limited supply of OBGYNs, lack of training in abortion provision, and the high rates of maternal mortality in the country, informed the government’s decision to prohibit CO. Dr Daba stated that, prior to its prohibition, CO had become a "significant barrier to access a safe and timely abortion" in Ethiopia. CO came to be viewed as a refusal to uphold the the rights of women, girls and pregnant people.

In the current context, Dr Daba explained that for OBGYNs in Ethiopia, the prohibition of CO is not seen perceived as forcing health workers to perform abortions, but rather they believe they are serving their duty as health care providers. Despite the prohibition of CO, there are still a number of barriers for pregnant people to access abortion care. Due to “stigma and fear, many pregnant people still access abortion care, often unsafely, outside of the health system”.

Lack of accountability for failure to regulate 'conscientious objection'

As well as exploitation of CO by health care practitioners, institutions endorse this through their failure to implement accountability mechanisms.

According to Dr Priyankur Roy, Representative for India at the World Association of Trainees in Obstetrics and Gynecology (WATOG), “physicians know that refusing to perform a pregnancy termination while alleging CO will have no consequences.” He adds that, by contrast, many health care practitioners fear negative social or legal consequences from performing abortions. Thus, they use CO as an excuse to deny this essential service, failing to fulfil their “professional and ethical obligation of providing safe abortion services”.

While working in Christian hospitals that do not support abortion, Dr Roy found that “sometimes extreme persuasion, especially in dire medical emergency, is required to perform an abortion”. He highlighted that medical staff have to contend with opposition from both the administration and their colleagues if they want to perform an abortion.

Dr Roy added, “if you look at the refusal of emergency care for a patient who absolutely needs us, I feel that CO is against our basic principles. It is against the Hippocratic Oath. We need to take care of our patients, and that duty has to be followed whatever the costs.”

Changing mindsets: OBGYNs as advocates for change

Dr Roy and WATOG believe that education is essential for turning the tide:

Educating and learning during the training period will go a long way in ensuring that trainees support women’s rights. We should work to disseminate some basic ethical principles, which is clearly stated in the FIGO Committee of Ethical Aspects of Human Reproduction and Women's Health.

We should also disseminate evidence showing that making legal abortion more broadly available does not increase the abortion rate, but it does reduce maternal mortality and morbidity.

Dr Félix Essiben, OBGYN at Yaounde Central Hospital Cameroon, explained that, to him, there remains a dilemma between respecting the freedom of women and girls to choose to interrupt a pregnancy and the freedom of the health care practitioner to ‘conscientiously’ object within the context of the law. He added that “there will always be those who oppose the act of abortion, and this must be respected.”

However, he also added that there is a need to build a nurturing environment that reduces the stigmatisation of abortion, allowing for the reduction of preventable deaths and for “people to open their hearts to abortion”. He stressed the importance of having protocols in place, such as a referral mechanism, to ensure that women and girls’ rights to abortion care are not violated.

Dr Essiben advised that building an ecosystem in which abortion care is de-stigmatised – both for practitioners that perform abortions and for the people that seek them – requires training to sensitise health care practitioners. This will enable better access to abortion care and services overall. Furthermore, he shared the importance of "training practitioners and conducting advocacy and lobbying, so that abortion will no longer be as restrictive as it [currently] is."

The need for systemic change

Dr Jaydeep Tank, Chair of FIGO’s Committee on Safe Abortion, recognised the role that patriarchal power structures have in governing, shaping and informing the implementation – or denial – of safe abortion services within the medical profession. As highlighted by Melissa Upreti,

We have a predominantly biomedical model that is very top-down paternalistic and it operates in a larger ecosystem of very patriarchal structures, laws, policies and norms. One thing to consider is what are the steps that need to be taken by the state and by other key actors to start shifting things to make it more respectful of the individual (woman or girl), [her] autonomy, decision-making [and] bodily integrity.

A UN Working Group on Discrimination Against Women report, Women’s and girls’ sexual and reproductive health rights in crisis, urged states to implement changes to oppressive structures:

Legal safeguards and protocols that ensure privacy, confidentiality and free and informed consent and decision-making, without coercion, discrimination or fear of violence, are necessary to guarantee the equal enjoyment of sexual and reproductive health rights for women and girls.

The stigma often assigned to sexual and reproductive health conditions, such as abortion is rooted in discriminatory gender stereotypes and patriarchal norms that must be dismantled through appropriate policies and interventions.

Key Strategies for OBGYNs to become conscientiously committed to safe abortion

FIGO has identified the following as key strategies to engage in and to promote engagement by member societies.

- Inclusion of sexual and reproductive health and rights including safe abortion, in pre and in-service training for health care practitioners.

- Lobby and advocate for stricter regulation and accountability of CO in facilities whereby it cannot be used to deny care in the care of emergency situations or for post-abortion care; also that it cannot be used by institutions or individuals other than those directly providing the abortion.

- Strive to end discrimination faced by patients who seek access to safe abortion services and those who provide these essential services and create a movement of health care providers ‘conscientiously committed’.

- Advocate for better regulation and monitoring of governments’ sexual reproductive health rights obligations eg on the implementation of access to abortion-related goods and service which includes access to information, and laws and standards that promote and protect women and girl's autonomy, privacy and informed consent central to all sexual reproductive health laws and policies.

- Integrate the recommendations from the UN Working Group on Discrimination Against Women reports, in addition to other expert UN groups, within their own advocacy calls.

Watch the full webinar here.